Olena Smaha

An exceptionnal contemporary art form rooted in the tradition of Slavic iconography

Olena Smaha (Ukraine) exhibited her paintings at Pigment Gallery, in Barcelona. Brief introduction to an exceptionnal

Paul Evdokimov famously wrote that “abstract art originates from iconography, Islamic

How can we follow the flow of tradition in a world that does not subscribe anymore to its codes? How can the eternal light that bathes the sacred figures reach down to us, when our daily lives are constantly bruised by gratuitous violence, as witnessed everyday in Ukraine, and recently too in Barcelona?

Olena’s icons are, from this point of view, deeply relevant. It is always tempting for an artist to reproduce the forms that made sense in the past, but Olena Smaha found the way to an authentic new language — and the word “language” is not used lightly, since an icon is written and not painted. Iconography is about writing the Word.

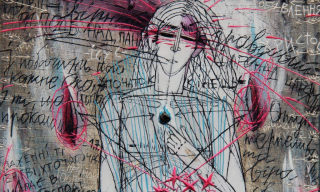

Even though the human figure is predominant in her icons, nothing is more foreign to Olena’s work than a fascination for the sensible nature of things. The written elements and the archetypical look of her figures remind us that the iconic similitude is always ruled by the hypostasis (the person) and its already-spiritualized body. Nudity, for instance, acquires here its full meaning, even though it is traditionally banned from the canons of sacred art. In reference to the Son of Man exposed to the crowd’s humiliations, the body recovers the sacramental meaning it had in its original innocence. Contemplated in this light, it acquires a symbolic dimension opening up to the person in its entirety.

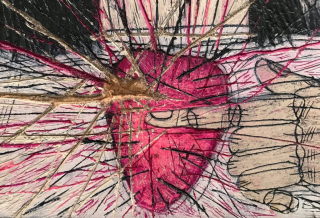

A number of details, such as the rose-colored cheeks (betraying the inner workings of love) or the use of verbal icons, show how seriously the artist is committed to the ancient tradition of Slavic iconography, when Kiev was the heart of Russia. Luz was undoubtedly one of the most important works in the exhibition at Pigment Gallery. While its formal composition follows the canons of the most ancient representations of the Transfiguration, it is also, in a certain way, revolutionary. Indeed, the boldness of the characters’ depiction, the seemingly chaotic ballet of lines (sometimes bordering on “rough art”), the expressive contrasts and the overload of undecipherable graffiti pay homage to street art.

This aspect of Olena’s work is what most manifests her responsibility as an artist. If you look at the ancient icons kept in Lviv, you will see that common people often engraved their names on their golden background. These engravings are an expression of devotion, the freedom of love overcoming the distance imposed by the sacred. On their rugged piece of wood, devoid of any aesthetic self-indulgence or seduction, the figures seem to lean in our direction (they use the traditional “inverted perspective” of icons) with an inexpressible pain. The work of clarification is performed with such intense perfection that each image seems, at the same time, the expression of a cry and of a supernatural love.

The simultaneous perception of a suffering echoing in eternity and of an inviting tenderness construes the true meaning of salvation and beauty, even though the beauty at stake is a wounded beauty. The contemporary man, especially when he experiences suffering, can no longer be satisfied by the empty aesthetic, sweet or dry, of canonical rules and ideas. He needs a naked presence, in its simplicity, in its uncompromising message. He needs being. Love alone can offer this, as it brings together knowledge and adoration, word and silence, beyond the dead ends of power and utilitarianism, and endowing the sacred with its most urgent performative dimension.

Many artists use forms in order to achieve an aesthetic result attuned to their tastes or to the expectations of their time, but very few are those who open for us the deepest recesses of their soul. These are the ones who truly enable us to perceive the crux of our time. At this point in history, Olena’s works seem to prophesies the destruction of our world and its re-foundation in mercy.